Role in Indian Freedom Movement

- Home

- Freedom Movement

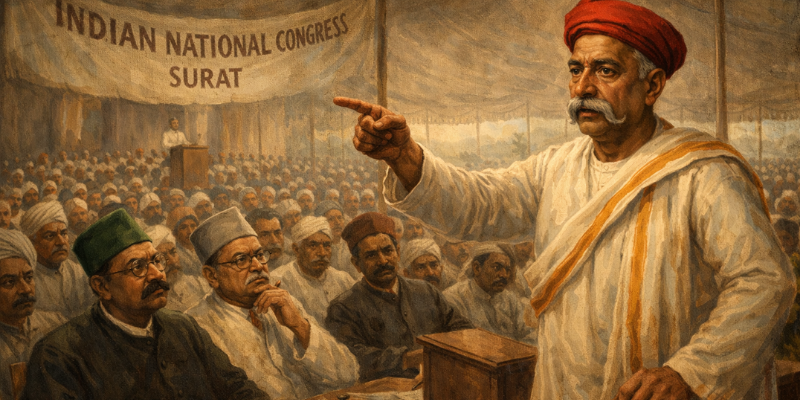

Early Congress Leadership

Tilak emerged as a bold voice in early Congress, pushing assertive nationalism and demanding Swaraj, shaping India’s political direction and awakening mass participation.

Bal Gangadhar Tilak played a pivotal role in the early leadership of the Indian National Congress, transforming it from a moderate discussion platform into a forceful national movement. He strongly opposed the slow, petition-based approach of early leaders and insisted that India’s freedom must be claimed through mass participation and fearless resistance. Tilak’s famous declaration, “Swaraj is my birthright and I shall have it,” electrified the nation and redefined the goal of the Congress.

Tilak led the Extremist faction, along with Lala Lajpat Rai and Bipin Chandra Pal, encouraging the youth and common citizens to join the freedom struggle. His leadership inspired widespread political awakening, public mobilization, and assertive strategies such as boycott and Swadeshi. Tilak’s bold vision laid the foundation for future leaders like Gandhi, transforming the Congress into a movement rooted in national pride and civil resistance.

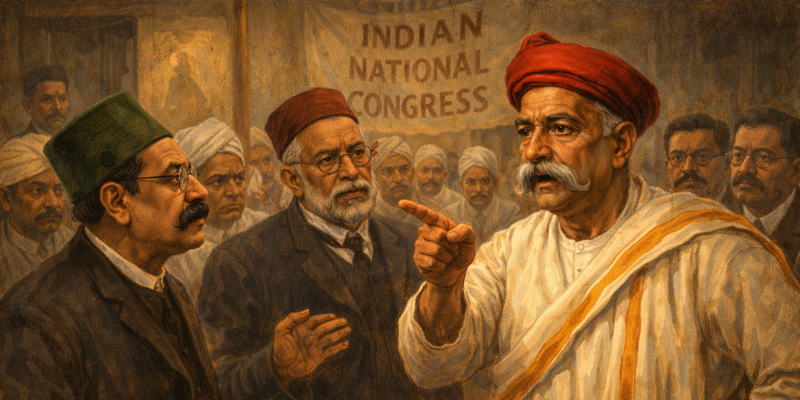

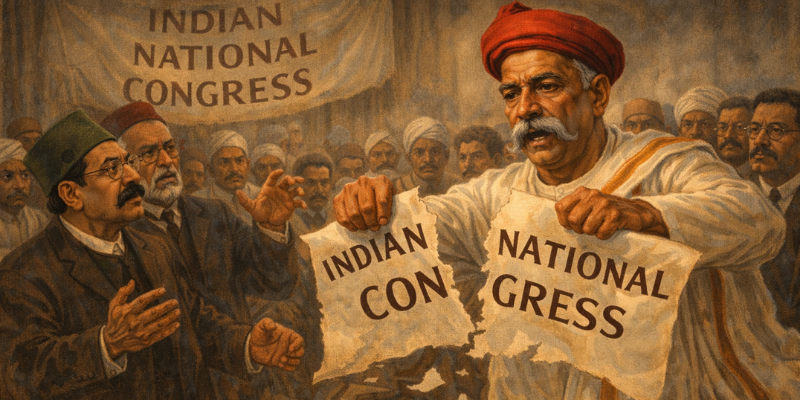

Surat Split of 1907

The 1907 Surat Split divided Congress into Moderates and Extremists, marking a major ideological battle over methods to achieve Swaraj.

The Surat Split of 1907 was a turning point in the Indian National Congress. Deep disagreements emerged between the Moderates, led by Gopal Krishna Gokhale, who believed in gradual reform through petitions and negotiations, and the Extremists, led by Bal Gangadhar Tilak, Lala Lajpat Rai, and Bipin Chandra Pal, who demanded immediate Swaraj through assertive national action. The conflict reached a breaking point during the 1907 Congress session in Surat, where intense disagreements over electing the party president led to physical confrontation and ultimately the split of the party. This event reshaped India’s freedom struggle, energizing mass participation and laying the foundation for a more determined and revolutionary approach toward independence.

Imprisonment (Mandlay Jail in Burma)

Bal Gangadhar Tilak’s imprisonment in Mandalay transformed him spiritually and intellectually, shaping his nationalist philosophy and deepening India’s freedom struggle.

Conditions & Impact

Bal Gangadhar Tilak was arrested in 1908 for his writings that inspired revolutionary nationalism and sentenced to six years’ imprisonment in Mandalay Jail, Burma. The harsh climate, extreme heat, isolation, and strict surveillance made his imprisonment physically painful and mentally exhausting. He suffered from poor health, inadequate medical care, and complete separation from his family and political circle. Despite these severe hardships, his resolve never weakened.

The imprisonment proved to be a turning point—not a punishment. Tilak used the solitude to reflect deeply on India’s struggle and to strengthen his ideological framework. The experience sharpened his belief that freedom was the birthright of every Indian and must be achieved through unity, self-discipline, and sacrifice. His time in Mandalay transformed him into an even more powerful and spiritually grounded national leader, respected across political divisions.

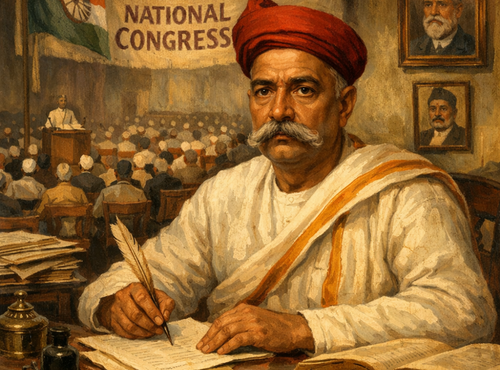

Composing Gita Rahasya

During his imprisonment, Tilak devoted himself to studying the Bhagavad Gita, analyzing it from a philosophical and practical perspective. Contrary to traditional spiritual interpretations that emphasized renunciation, Tilak argued that the Gita teaches Nishkama Karma—selfless action driven not by personal desire but by duty. This interpretation became the philosophical foundation of his book ‘Gita Rahasya’, written entirely by hand inside Mandalay Jail.

The text emphasized that true spirituality lies in fearless action for the welfare of society, not in withdrawal from life. Completed under extremely difficult conditions, the manuscript was later published after his release and became a guiding force for the freedom movement. It influenced countless leaders including Mahatma Gandhi, Lala Lajpat Rai, and Subhas Chandra Bose. Gita Rahasya remains one of Tilak’s most powerful intellectual contributions, merging devotion with national service.

Home Rule Movement (1916)

Tilak and Annie Besant launched the Home Rule Movement in 1916, inspiring nationwide demand for self-governance and mass political participation.

Collaboration with Annie Besant

Bal Gangadhar Tilak returned to active politics after his Mandalay imprisonment and recognized the urgent need to unite moderate and extremist nationalists. In 1916, he collaborated with British-origin social reformer and educationist Annie Besant, who also believed in India’s right to self-rule. Together, they founded the Home Rule Movement, modeling it after the Irish Home Rule struggle. Their partnership symbolized unity across ideology, religion, and nationality.

Tilak established the Home Rule League in Maharashtra, Karnataka, and Central Provinces, while Besant organized the movement in southern and eastern India. They organized public meetings, published pamphlets, and traveled extensively to spread political awareness. Their combined leadership revived the national spirit and demonstrated that freedom could be achieved only through disciplined, nationwide participation. This alliance reshaped India’s political landscape and laid the foundation for future mass movements led by Gandhi.

Mass Political Awakening

The Home Rule Movement marked a new era in India’s freedom struggle by transforming political agitation into a mass movement. For the first time, people from small towns, villages, students, women, lawyers, and industrial workers actively joined the demand for self-government. The slogan “Swaraj is our birthright, and we shall have it” echoed across the nation, turning passive subjects into conscious citizens.

Through fiery speeches, newspapers like Kesari, and extensive mobilization, Tilak inspired people to view political participation as a national duty. The movement created a sense of unity, encouraged local self-rule committees, and demanded the transfer of political power to Indians. Although the British government suppressed the movement by arresting Annie Besant and restricting activities, the spark it ignited permanently changed Indian politics. It paved the way for the Non-Cooperation Movement and strengthened the call for complete independence.